3 A Typology of Research Questions

3.1 Introduction

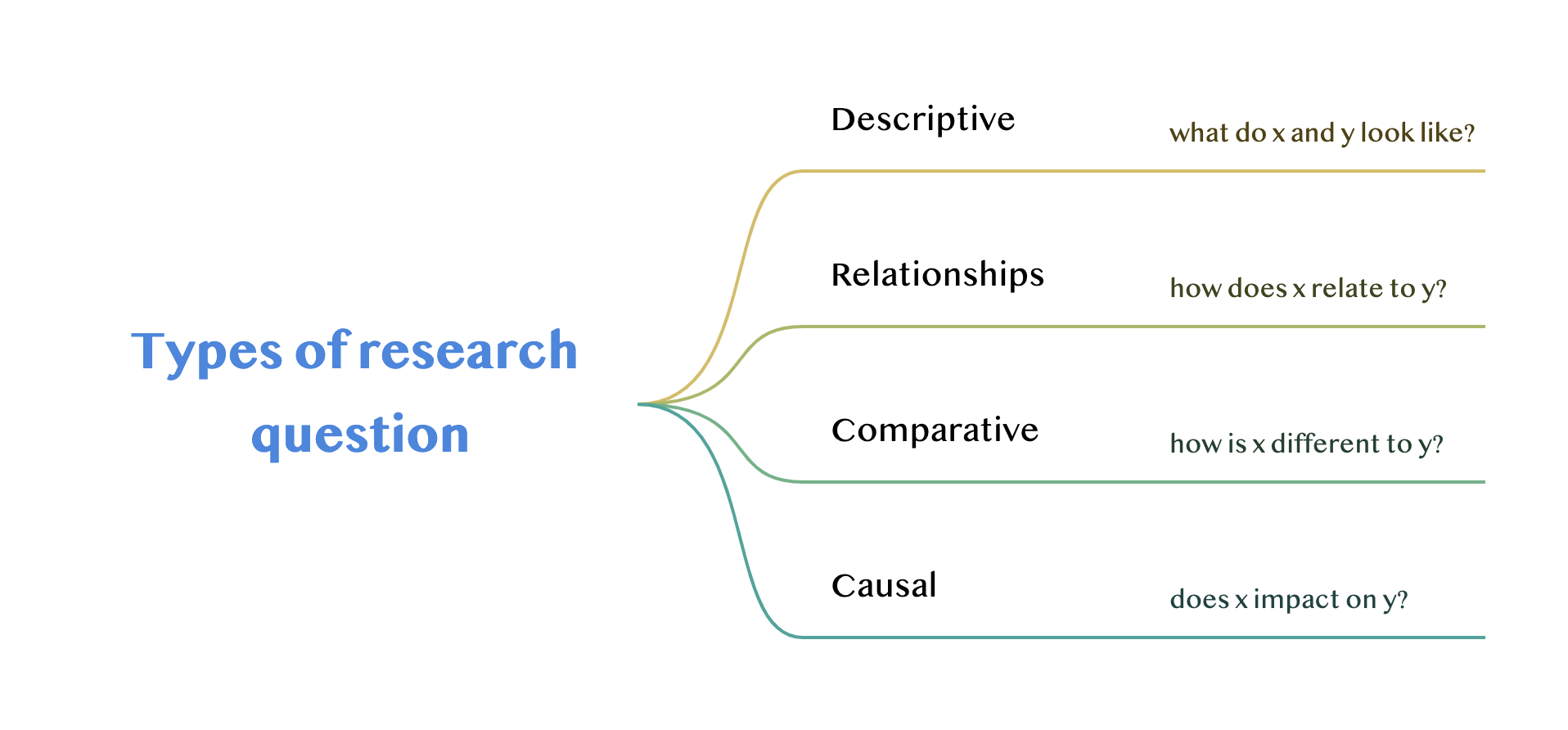

Developing our understanding of the three basic ‘forms’ of research (descriptive, predictive, prescriptive), in this section we’ll identify four ‘types’ of research question that are commonly used in the social and physical sciences.

3.2 Type One: Descriptive questions

Previously, we identified ‘descriptive’ research as being one of the main forms of research in sport. These kinds of questions have a number of useful functions, including:

Understanding basics

At the foundation of any research is the comprehension of the basics of the topic under investigation. Descriptive questions attempt to identify core attributes, including clarifying the essential properties and characteristics that delineate the subject.

Following this, establishing definitions is of paramount importance. By rendering clear and exact definitions, a shared understanding of crucial terms and notions is assured.

Lastly, the act of gathering descriptive data entails the accrual of information that exemplifies rudimentary facets of the phenomenon, whether it be its size, hue, behaviour, or any other inherent aspect.

Setting the scene

Before getting too far into a topic, it’s helpful to be aware of its backdrop. For example, providing historical context can illuminate the progression or metamorphosis of the topic across different time periods. Coupled with this is the act of outlining the current state, which involves a depiction of the subject’s present-day status, integrating any novel shifts or evolutions that you’ve identified.

Beyond just the subject, it is also vital to spotlight relevant contributory factors. By noting external influences or circumstances, we can gain insights into external variables affecting the phenomenon under scrutiny.

The term ‘covariate’ will be used across this module. Basically, this is something that varies in addition to the variable we are interested in, and whose influence we may need to take into account.

For example, we might be interested in hours of sleep and its impact on performance, but ‘quality of sleep’ is another covariate that we might also need to consider.

Identifying patterns

A core element of descriptive research is the discernment of patterns. This commences with analysing trends, wherein the data is sifted through to discern any consistent evolutions or shifts across temporal scales.

To achieve this, categorising data is crucial. Through the compartmentalisation of data into significant clusters or sets, pattern recognition is facilitated. We’ll deal with this in much more depth when we encouter Factor Analysis and Cluster Analysis later in the module.

However, not all data aligns neatly, so noticing anomalies becomes essential. Outliers or unexpected values can sometimes unearth underlying patterns or interrelations, often missed in broader overviews.

Establishing norms

‘Norms’ act as the compass guiding research, offering a standard for evaluation. This begins with defining typical characteristics, delineating the usual or median traits of the subject, thereby setting a reference.

After this, the determination of the ‘range of variation’ comes into play. By pinpointing the conventional scope of variability, a definition can be crafted for what is deemed regular or anticipated.

With established norms in place, a reference benchmark is set, paving the way for studies in the future, be it temporal comparisons or juxtapositions across diverse milieus.

Reflect

Considering the importance of descriptive questions in research, how can sport researchers utilise these principles to gain a comprehensive understanding of an athlete’s performance or a team’s dynamics over a season?

3.3 Type Two: Relationship-based questions

Moving beyond description, researchers often ask questions about the relationships between the variables they have collected.

Exploring correlations

Research often seeks to discern relationships between variables. The initial step, identifying variable relationships, involves ascertaining which factors appear to fluctuate or evolve in unison.

However, determining whether these relationships matter necessitates using statistical methods. Techniques such as Pearson’s correlation coefficient can be pivotal in quantifying the vigor of such associations.

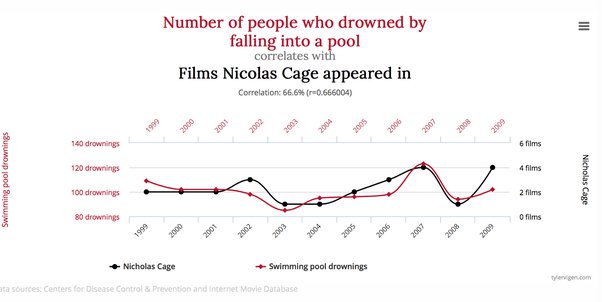

It’s always important to remember the distinction to be made is between correlation and causation. A mere correlation doesn’t necessarily signify a causative relationship, warranting further analysis to validate any cause-and-effect link (as the following image demonstrates):

Understanding directions of relationships

To explore further into the nature of relationships, we first need to identify dependent and independent variables, essentially discerning which factor might be influencing the other.

This aids in analysing positive and negative relationships, shedding light on whether the variables shift in tandem (a positive bond) or in conflicting directions (a negative bond).

Further insight can be sought using experimental design. By manipulating one variable and scrutinising alterations in another, researchers can ascertain the directionality of their relationship.

Assessing the strength of relationships

Measuring the robustness of relationships is a fundamental step in relationship-based inquiries. Quantifying relationships can be achieved via statistical methodologies that decipher how intimately two variables correlate.

A critical tool we’ll learn about in this module is interpreting the coefficient of determination. R-squared values are instrumental in delineating the percentage of variability in the dependent variable that can be predicted from the independent variable(s).

Understanding the difference between a dependant variable (DV) and an independent variable (IV) is vital in this module.

I tend to think of DVs are ‘outcomes’ that we are interested in, and IVs as ‘predictors’ that we suspect might be important in determining the outcome. The dependent variable depends on the independent variable or variables.

If you run fast on a treadmill, your heart rate increases. The speed of the treadmill is the IV, heart rate the DV. Your heart rate depends on the speed of the treadmill.

Nevertheless, considering the context is paramount. The intensity of a relationship can be influenced by the milieu and other pertinent factors.

Identifying ‘moderating’ or ‘mediating’ variables

Some variables play intermediary roles, affecting the main relationship under study. This brings in the exploration of moderating variables, which can impact the strength or direction of the association between primary variables.

Conversely, mediating variables can operate as conduits, offering explanations for existing relationships. To capture the intricacies of such variables, conducting multi-variable analysis becomes vital.

dvanced statistical procedures enable the simultaneous analysis of relationships among three or more variables, enriching the depth of insights.

We’ll learn more about mediating variables when we explore Path Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling later in the module.

Reflect

How can sports scientists harness the principles of relationship-based questions to determine the effect of training methodologies on an athlete’s performance, considering other potential moderating variables like diet or sleep patterns?

3.4 Type Three: Comparative questions

Group comparisons

Group comparisons are essential when discerning differences and similarities among distinct groups.

First, it’s crucial to identify which groups should be compared based on the research inquiry. Once identified, researchers can start analysing between-group differences, looking for any disparities in traits, behaviours, or results.

However, beyond understanding differences, assessing within-group similarities is just as vital. By doing so, we can guarantee that the comparisons are meaningful and that individuals within each group share enough commonalities to make the comparison valid.

Before-and-after comparisons

Often, researchers want to understand the effect of a specific event or intervention. This requires establishing a baseline, which captures the state of the subject prior to the intervention. Post-intervention, the focus shifts to assessing impact, gauging any modifications that arise.

It’s important to control for external factors. This ensures that any observed alterations can genuinely be ascribed to the intervention in question and not to unrelated external influences.

Cross-cultural comparisons

Sports research frequently crosses cultural boundaries, demanding special considerations. Primarily, it’s essential to truly understand the cultural contexts of the groups being compared.

This ensures that comparisons are both accurate and meaningful. From there, it’s about identifying cultural variables; pinpointing which facets of culture are most pertinent to the study and figuring out their measurement.

However, conducting research across cultures comes with its ethical considerations. It’s important to approach such studies with respect, acknowledging potential biases and ensuring that the research remains ethical throughout.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is a technique that compares one’s performance against industry standards or best practices.

The process begins by selecting appropriate benchmarks that are both pertinent and dependable. Once these are set, the next step involves analysing performance gaps, pinpointing areas where one’s performance either lags behind or surpasses the benchmark.

But the ultimate goal of benchmarking isn’t just comparison for its own sake; it’s about utilising these insights for amelioration. The information gleaned should be a catalyst for driving enhancements and fine-tuning performance.

Reflect

How might a researcher in sport employ the comparative methods described above to evaluate the effectiveness of two different training regimens on athletes from diverse cultural backgrounds, ensuring that the comparisons are both meaningful and respectful?

3.5 Type Four: Causal questions

Establishing cause-and-effect

Central to causal research is the establishment of a ‘cause-and-effect’ relationship. To start, researchers must demonstrate temporal precedence (what happens first?), ensuring that changes in the presumed cause indeed happen before the resultant effect.

It’s essential to eliminate alternative explanations. By ruling out other potential causes for the observed effect, we can strengthen the validity of the cause-and-effect claim.

Experimental design

Experiments are powerful tools in establishing causal relationships. Key to this approach is the use of control groups, which provide a baseline against which the experimental group’s results can be compared.

Furthermore, randomising assignments is essential. By assigning participants to groups randomly, researchers control for any confounding variables that might skew results.

Equally important is ensuring replicability. For the results to be valid and broadly accepted, other researchers must be able to replicate the experiment and achieve similar outcomes.

Longitudinal studies

Longitudinal studies offer insights into how things evolve over extended periods. By tracking changes over time, we can discern long-term effects or patterns.

Analysing developmental trends allows us to understand how relationships between variables might shift as participants grow older or as conditions change.

However, longitudinal studies come with challenges, such as participant drop-out or attrition. To counter this, we need strategies in place to keep participants engaged and ensure the continuity of data collection.

Controlling for confounding variables

In causal research, confounding variables can distort results, making it crucial to control for them. Initially, we must identify potential ‘confounders’; variables that might misleadingly appear related to the observed effect. Once identified, we can employ statistical controls to keep the confounders’ influence in check.

Reflect

Imagine you’re a researcher aiming to determine if a new training regimen directly improves athletes’ performance. How might you design an experiment to establish a cause-and-effect relationship, considering the components of experimental design and the need to control for confounding variables?

3.6 Reading

The following is a useful resource that develops some of these concepts more fully. It’s available via the University library using the module myplace link:

- Andrews, R. (Richard J. ). (2003). Research questions. Continuum.